MARTIN'S VOYAGE OUT

ON THE STEBONHEATH

The ‘Stebonheath’ was a three-master of 926 tons built in Hull in 1842-3, being 151 feet in length, 36 feet 7 inches in breadth, and with a depth of 23 feet. Her home port was London and some of her earlier voyages were to Bombay and to Halifax. The owners at the time of Martin’s voyage were Messrs. Wilson & Co of London. In 1851, when owned by Wilson and Co of London, the Stebonheath was sheathed in yellow metal and received a ten year A1 certification from Lloyds

The ‘Stebonheath’ was a three-master of 926 tons built in Hull in 1842-3, being 151 feet in length, 36 feet 7 inches in breadth, and with a depth of 23 feet. Her home port was London and some of her earlier voyages were to Bombay and to Halifax. The owners at the time of Martin’s voyage were Messrs. Wilson & Co of London. In 1851, when owned by Wilson and Co of London, the Stebonheath was sheathed in yellow metal and received a ten year A1 certification from Lloyds

They set sail on Wednesday, 30/9/1857, and the ship had barely left the wharf at Portsmouth before a few of the passengers felt seasick. And as they moved further out into the Channel and took a bearing south towards the Bay of Biscay, the sense of desolation as the last sliver of land dipped below the horizon, combined with the appallingly cramped conditions below decks in their quarters soon had them all heaving. Martin shared a lower bunk with Michael Hannon a 24-year-old farm labourer who was also from Roscommon, and they quickly came to an agreement with those in the upper bunks. In return for a loud warning when anyone in the upper bunks was going to puke, they were delegated to clean the mess off the deck and empty the night buckets. A further complication was that any of the emigrant’s meagre belongings not well stowed or tied down came loose with the motion of the ship, tumbling down on any unfortunate in their path and adding to the general confusion below decks.

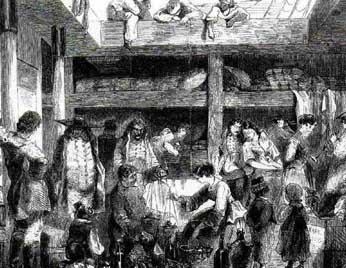

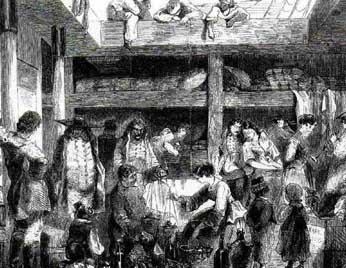

Messes were set up on the Sunday The passengers were divided up into groups of six to a ‘mess’, with each mess having an appointed mess captain who was the only one in the group allowed to enter the galley. Here the emigrants’ cooks, Sydney Prendergast (57) and I. Partridge (29), together with James Wilson (21), the steward, were in charge of cooking the rations.

A mess form had been issued to each adult male emigrant, thus they knew their rights, at least as far as quantities were concerned. But between an emigrants ‘rights’ and his mouth were various obstacles. Because of the rapaciousness of some provisioning companies and the ship owners - some ships supposedly provisioned for the entire voyage were sometimes forced to make unscheduled calls into ports for additional supplies. Other obstacles were the filching of supplies by unscrupulous officers at sea, the inexperience - especially among the single men - in preparing dishes, and the frequent crankiness of cooks who were supposed to cook what was taken to them. For example, the ‘biscuits’ which figured so largely in the emigrant diet were four inches square and at least an inch thick, and baked so hard, presumably to preserve them, that they were impossible to bite into without previous softening in water or tea.

|

|

|

BELOW DECKS

|

Rations were served out once a week, and meat twice a week, by the third mate, Henry White (21). Each mess had a number and in the mate’s book was entered the quantities to be supplied. As a number was called, the respective mess captain stepped forward to take what was coming. Because of the numbers onboard, there was never-ending cooking going on and emigrant diaries abound with descriptions of dishes prepared by steerage passengers - some results comic, some pathetic, others showing the ingenuity of some passengers and the helplessness of others. The greatest range of ‘botched’ dishes was undoubtedly prepared by the single men.

"I asked an Irishman who had just put some dough into a tin to be baked whether he had greased the tin. He said not. I replied that you must do so or the cake will stick; and believe me the fellow actually greased the outside instead of the inside, in perfect ignorance." (Edward Snell on board the ‘Bolton’, 1849).

As it was Surgeon William Johnson Rowland’s seventh voyage, he was an experienced hand who quickly took charge. The sick were coaxed to eat a pap of ship’s bread soaked in water and washed down with sweetened tea and encouraged to take the air on deck. But most were feeling too sorry for themselves to shift from their bunks. The moaning and groaning below decks and the all-pervading smell of vomit added to the general malaise. Next on Surgeon Rowland’s agenda was hygiene, and daily inspections were instituted to ensure all below deck quarters were scrubbed down, night buckets emptied and rinsed out in seawater, and no foodstuffs left lying around to attract vermin. The passengers were taken up on deck in groups of fifty or so to strip off and wash in seawater, and every week provision was made for the washing of clothes.

LIFE ON BOARD

IN THE BAY OF BISCAY

The Stebonheath left Plymouth on September 30 (last year) but in crossing the Bay of Biscay she was caught in a terrific hurricane on October 6th, and while laying-to a heavy sea broke on board, making a clean sweep fore and aft. The bulwarks, deckhouses, &c., and all the boats were at once swept overboard, the port quarter galley stove in, and the cabin and bulkheads carried away by the force of the water coming through the opening. Skylights, companion, and everything above deck, with the exception of the masts, was completely destroyed;

Extract from The Sydney Morning Herald, Monday,1 March 1858fortunately only one boy was drowned. Captain Connell was therefore compelled to bear up to the nearest port to repair damages, and on this 6th. October he made Pauillac, a small sea town about thirty miles from Bordeaux. Here he remained until 1st. November since when he has had a fair passage.

The storm lasted a day and a night, all Monday night and into Tuesday, and “ was it to be wondered at such a time . . . when almost everyone saw nothing but death’s grim visage confronting them . . . , amid the shrieks of the timid, and the half-stifled groan of the boldest, that some of those (single women) who were alarmed would rush into the compartments of the married people for some sort of consolation or assurance of probable escape? Surely it was no great sin for a sailor at such a time to inform them that there was more fear than danger; and yet the regulations were so strictly enforced, that two of the sailors were handcuffed for speaking to them” (taken from passengers’ letter to SMH of 9/3/1858)

At this fearsome time, with the wind howling in the rigging as the ‘Stebonheath’ hove-to on shortened sails, able seaman, James Parker (16), was swept overboard and swiftly carried out of sight in the turbulent waters.

After the sheer terror of the storm, there was great relief and excitement among the passengers as none of them had ever been outside the British Isles let alone a foreign country where English was not the common language! The call at Pauillac, in the Medoc wine region on the River Gironde, was a prolonged one of three weeks. Many of the passengers wanted to go on shore but were prevented from doing so; many wanted to return to their friends; this also being refused, they wanted to signal for the English Consul, to petition him on the subject of their grievances. Presently they saw a boat coming and thought it was the Consul, but it turned out to be the captain who had been to Bordeaux. Some of the passengers with a little cash or trinket to barter managed to purchase fresh fruit from hawkers on the wharf.

This enforced stay at Pauillac saw the beginning of the undoing of relations firstly between the officers and the crew, and then between the officers and the passengers. The doctor was the first to show his true colours being habitually drunk to the extent that he could scarcely make his way up the ship’s gangplank. On one occasion there was mutinous conduct among the seamen when all of them with the exception of the boatswain, James Wilson 40, and the carpenter, Robert Standidge 36, and the chief officer, John Dray 31, were ashore. The boatswain and the carpenter got very drunk and, on the drunken return of the doctor, commenced abusing both him and the chief officer, telling the latter he was no sailor. The matron, Jane Chase, and some of the women were on the poop deck at the time and the matron, seeing trouble brewing, prudently ordered the women below and locked them in. The boatswain assailed the doctor and a desperate struggle took place, an effort being made to throw the doctor overboard. The boatswain and the carpenter were dealt with at Pauillac under the Passengers’ Act, and their places were supplied by Frenchmen.

Captain Connell was by then about 50 years of age and too mild-mannered a person to manage an emigrant ship. The chief officer was efficient, but the second officer, Charles Pycraft 31. and the third officer, Henry White 21, proved themselves bad men who on many occasions stood by watching while the matron was grossly insulted and assaulted by the sailors. (From the evidence of Jane Chase given at the inquest of Ann Cox , 5/3/1858)

From then on the doctor was frequently seen in a state of intoxication. on one occasion falling down the steps leading up the hatchway to the deck three times. On another occasion the doctor came down between decks in the middle of the night and called the single men up , who thinking there was a storm, jumped up, dressed and rushed up on deck to be confronted by the doctor who told them they could go back to bed as he burst out laughing at them. (From a public meeting of passengers - Sydney 10/3/1858)

* * * * * * * *

Meanwhile, Matron Jane Chase had been showing her prejudices right from the first week when most aboard were still suffering the combined effects of seasickness and the feeling of having left ‘good old Ireland’ forever. She had had the misfortune to have travelled with the English girls on the train from London to Plymouth. During the trip, she had observed that a few of the girls were ‘tipsy’, and one girl, in particular, was seen to have her arm around the neck of a guard! From this incident, she had decided that most, if not all, of the single girls, were the lowest of the lower classes and began to treat them accordingly. She was a self-righteous and self-serving religious bigot who purchased apples, onions, chocolates and eggs while in France and sold them during the voyage for five times what she paid for them. She constantly abused the unmarried girls, calling them ‘humbugs’ and ‘ten shilling paupers’. During the stay in Pauillac it was reported to the matron that one of the girls was in the forecastle with the sailors, but after she had made a diligent search there was no trace of her. She then advised the doctor who took his constables and found her.

Miss Chase later saw the girl carried past her cabin by some men to her berth and could smell the liquor on her. It was after the delay in Pauillac that she developed the paranoia that all the single girls were fraternising with the sailors.

Now the only way the sailors could get to the girls was through the married quarters, which would have been impossible without the connivance of a goodly number of the married passengers, but this did not allay her fears. Even though the single girls comprised a few mothers with their daughters, she was still convinced of ‘goings on’ and dragged the doctor down to inspect the bulkhead separating the girls’ quarters from the rest of the ship. The doctor at this time was very tipsy; he had fallen in the water and had to be picked up in the boat; he knocked down the bulkhead which separated the single women from the other part of the ship, and said “this gingerbread work won’t do”; the captain stood by and laughed; he was several times drunk, and got them up as described in the middle of the night, and then laughed at them; he used also to threaten what he could do with them when he got them in the colony, as though he was the king of Australia. (As reported at ‘Meeting of Passengers’ on 10/3/1858)

Miss Chase had a habit of telling the girls ‘they only wanted a man to lie between each of two of them and if she kept a floating brothel, that would suit them.’

Miss Chase threatened to send the girls up the country on their arrival, saying before now she had separated daughters from their mothers, and sent them off without an opportunity even of saying goodbye; she also told them that “they did not know what it was like to be in the hands of Government, but they would see what the Colonial Government would do with them.”

Henrietta Jackson was a waiting-maid to Miss Chase, and she was on one occasion missed and supposed to have thrown herself overboard; at last Mrs. Lewis saw her coming on deck, and asked her where she had been; she said “nowhere”, and began to talk to Ellen Loughborough, who said the matron was an unfeeling creature. Miss Chase then accused Ellen Loughborough of encouraging Henrietta Jackson, and of concealing her. Some words ensued, and Ellen Loughborough was locked up on Monday afternoon, at 4 o’clock, and let out at 9 on Wednesday night. Henrietta Jackson was locked up, and not released until the day after Ellen Loughborough. Mrs Lewis saw Ellen Loughborough come out; she had had irons on; she had large wounds on her arms where the iron rust had eaten into them and Mrs Lewis was poulticing them right up to the time she left the females depot in Sydney. Ellen Loughborough told her she only got out by begging the matron’s pardon. The boxes in which these girls were locked up were too small to turn around in. They were described by other immigrants as being about 14 inches square, or about 14 inches by 19 inches, and not tall enough to stand up in. Those boxes were built by order of the doctor, with Miss Chase’s knowledge and consent. ‘Cramping-boxes’, as they were called, were widely used on the convict ships, but unheard of on a passenger vessel. On at least eight occasions, according to the later recollections of Miss Chase, there were girls punished (tortured?) in this manner. (From Meeting of Passengers 10/3/1858)

Thus the conduct of the Doctor and Miss Chase was tyrannical in the extreme and the passengers had decided that neither were fit to occupy their positions.

Nevertheless, in a situation where around 150 single women were thrust into close proximity, for several months, on board a ship, with a combined total of around 120 single male passengers and crew, despite the most stringent vigilance of Miss Chase and the doctor, nature was inevitably to follow its course. Most of the contact was restricted to frivolous conversation and furtive passing of notes, however, it is quite evident that some of the more forward girls managed to make contact of a carnal nature with some of the men; and this was to be the eventual undoing of poor Ann Cox. (See "Inquest")

Despite strenuous denials to the contrary, it is fairly obvious that Ann had been ‘interfered with’ during the voyage by one of the male passengers or a crewman, and the matron had made dire threats of what she and the colonial authorities would do to the girls who had misbehaved during the voyage. Several weeks before arriving in Sydney, Ann apparently fell down a hatchway and the hatch cover fell on her wrist severely injuring it. Unattended, the wound turned septic and, despite superficial treatment by the doctor, she was delirious and in a desperate state by the time the ship arrived in Sydney and had to be carried ashore to the hospital where she died the next day. The Coroner found that she had died from an “irritative fever” brought on by the injury to the wrist; and that she was recently pregnant.

At the subsequent coroner’s inquest, the matron Jane Chase, attempting to justify her and the doctor’s disregard for the passengers’ wellbeing during the voyage, gave slanderous testimony alleging all sorts of misconduct between the single females and the males on board.

* * * * * * * *

The next port of call was Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands off the Western Sahara desert of North West Africa. The weather was getting decidedly warmer and Captain James Connell ordered John Dray, the mate, to bring the passengers’ boxes up on deck from the hold so that they could get at a change of the clothing they had been wearing constantly since leaving Portsmouth.

The town was small, treeless and very tired-looking, and the land around it was precipitous, dry, inhospitable. For such an arid desolate place, Tenerife was known for its excellent water which came down from a spring in the interior of the island near a town called Laguna and was conducted through pipes of elmwood to a series of outlets dispersed along the short stone jetty.

The ‘Stebonheath’ anchored in the harbour and Captain Connell despatched the second mate, Charles Pycraft (23) together with a few seamen in the long boat to refill the water tuns. Since leaving Portsmouth, the ‘Stebonheath’ had consumed around 4,000 gallons of water and there were 26 of the 160 gallon receptacles to fill, with each one taking two and a half hours to fill. The system was quite ingenious and permitted the filling of six tuns at once. The longboat had been stacked with six to a side, and this required it to be constantly turned and returned as the tuns were part-filled to avoid capsizing.

Apart from song and dance, a group would sometimes stage a play; and the big ceremony of the voyage was always the “Crossing of the Line” when the ship passed from the northern to the southern hemisphere and King Neptune would come aboard to initiate those who had not crossed the equator before. Fearsome in swab wig and iron trident, shells and dried starfish entangled in his oakum beard, sewn into the flayed skin of a dolphin and stinking to high heaven in the tropical sun, the sea-god would bear down on the hapless neophytes flanked by grinning Jack-tar “mermaids” holding buckets of soap and gunk. The initiates were first clipped with scissors and lathered with a mop before being ‘shaved’ and ducked in a tub of seawater.

The passage times of the early sailing ships were wearyingly slow. Shipboard life became a world within a world, shut off from the rest of humanity. Departure from one’s homeland was trial enough, for most it was accepted as lifelong separation, never expecting to return.

The most consoling of events for the southbound passengers occurred when there was a chance meeting at sea with a homeward bound vessel. After an exchange by the masters shouting through megaphones comparing latitude and longitude and exchanging stale news from home and the colonies, there was an opportunity for the passengers to despatch mail to their distant families and a longboat was lowered for this purpose. Many being illiterate, they could only dictate hastily scrawled notes to those who were willing to transcribe them.

One passenger wrote, “I do not know one thing I felt so much as the loss of the North Star. Night after night as I watched it sinking lower on the horizon. It was like saying goodbye to Ireland all over again.”

Next was the run down to Capetown, where, as before, the passengers were not allowed to go ashore. The freshwater tuns were again refilled and some fresh produce was purchased to refill the ship’s stores. While in port the ship was continually surrounded by ‘bumboats’ selling every conceivable commodity and those passengers still with some money or goods to barter took advantage of this last opportunity to either supplement their diets or satisfy a craving.

Leaving Capetown, the ship was headed into the Indian Ocean where, for the first time on the voyage, they were to encounter windless conditions, and scorching sun. In the searing heat, with the ship totally becalmed on an oily sea, Robert Stanbridge, the ships carpenter, rigged canvas awnings from the stays to the shrouds or any handy projection to give some protection from the merciless rays of the sun. Some of the passengers also took to sleeping on deck.

Two things to remember about the immigrants; because they had become accustomed to great hardship, they were able to tolerate shipboard conditions on the way out that to us today would be intolerable. Secondly though, as harsh as there lives at home had been, few were really happy to leave. The devil you knew was usually preferable to the one you didn’t, and the colonies were literally at the end of the known world!

The horrors of the five long months of sea travel for the miserable landsmen cooped-up in low, ill-ventilated and overcrowded ‘tween decks were fit to be compared with those of the infamous convict ships. Losses through disease and malnutrition were in some cases worse than the record of the convict ships. Steerage passengers had to prepare meals for themselves and were often unable to do so through seasickness. Then the strongest maintained an upper hand over the weakest. In the many cases when passengers would not go up on deck, their health suffered so much that they were sapped of all energy and had not the strength to help themselves. Between decks was like a loathsome dungeon and when the hatches were opened under which the people were stowed like cargo, the steam and stench was like that from a pigpen.

So they passed the long weeks making ‘scrimshaw’, manufacturing seals, toothpicks, tobacco-stoppers, and other ornaments out of laboriously-carved bones; the sailors, being more experienced, showing the less-experienced passengers how it was done. A few of the more ingenious items were rings and brooches out of common (brass) buttons.

Fishing details were organised, and in the more clement weather groups would troll lines behind the ship, hooks baited with strips of canvas greased with pork fat. The catch was usually bonitos (Spanish mackerel) which were pounced upon with enthusiasm to vary their otherwise dreary diet of salt meat and corn meal ‘stirabout’.

Occasionally the sailors would catch albatrosses with baited hooks and a sounding line, dragging them screaming on board to slaughter and skin them; there being a market in England for these stuffed birds.

Passengers attempts to amuse themselves were encouraged by the ship’s surgeon and the night air was frequently filled with the sounds of music and dancing. Gambling was rife and covered everything from the little money they had to trinkets, tobacco, or items of clothing. And if there was a shortage of playing cards, bibles and prayer books were cut up to make them.

Christmas had come and gone during this period marked by a ‘special’ church service and a lacklustre attempt by the crew and passengers to introduce some merriment into the daily tedium.

Far south in the Indian Ocean, the sea could gain a height of forty feet - regular waves rolling in the direction of the wind and higher peaks and crests produced by crossing waves. The wind was so strong that it not only blew off the crests of the waves but seized on great masses of soaring peaks, cutting them off, and carrying them away. cutting visibility to several hundred yards in all directions. Four men at the helm struggling to keep the wheel under control as they endeavoured to counteract the sideways tendency of the ship’s bow; behind them a mountainous wave threatening to engulf the ship and all aboard her. The feelings of the hundreds of steerage passengers battened below can scarcely be imagined! All too many were inadequately clad, either from poverty or ignorance, not realising that a latitude of 50 degrees to 55 degrees south meant quasi-arctic conditions. Darkness fell around 4 p.m. and there were sometimes inches of snow on the decks, and the very rigging sheathed in ice. It was then that many a poor undernourished infant died. Their bodies stitched in canvas were consigned to the sea with a perfunctory service as the ship raced on in turbulent seas.

The Australian coast had been sighted and within a few days they were passing through They had been sailing for some weeks with a favourable following wind which the crew called the ‘roaring forties’, when, suddenly, there was news that the Bass Strait.

In the preceding weeks, there had been more distressing altercations between some of the female passengers and the matron, with the doctor intervening; and his doling out of such severe punishment earlier in the voyage to two of the single girls still rankled. All of the passengers were quite upset by the severity of the punishment for an apparently mild misdemeanour and grumbled amongst themselves but were all too cowed by the doctor and his assumed authority to speak out. Especially as both the doctor and the matron still threatened what would happen to any troublemakers once they reached their destination, inferring they had all sorts of influence with the colonial authorities. Poor Martin was still too young and too ignorant of the ways of the ‘outside’ world to be able to know what was right and normal as opposed to what was inhumane and abnormal. His short and painful life to date had been too filled with personal tragedy and trauma to have any idea how ‘civilised’ society comported itself, so he distanced himself from any dissent.

With Wilson’s Promontory on the port bow, they swung north and almost immediately encountered stiff nor-easterly breezes which required long tacking legs well out to sea as they made their way up the eastern seaboard with occasional glimpses of what appeared to be a very inhospitable coastline.

The ‘Stebonheath’ was a three-master of 926 tons built in Hull in 1842-3, being 151 feet in length, 36 feet 7 inches in breadth, and with a depth of 23 feet. Her home port was London and some of her earlier voyages were to Bombay and to Halifax. The owners at the time of Martin’s voyage were Messrs. Wilson & Co of London. In 1851, when owned by Wilson and Co of London, the Stebonheath was sheathed in yellow metal and received a ten year A1 certification from Lloyds

The ‘Stebonheath’ was a three-master of 926 tons built in Hull in 1842-3, being 151 feet in length, 36 feet 7 inches in breadth, and with a depth of 23 feet. Her home port was London and some of her earlier voyages were to Bombay and to Halifax. The owners at the time of Martin’s voyage were Messrs. Wilson & Co of London. In 1851, when owned by Wilson and Co of London, the Stebonheath was sheathed in yellow metal and received a ten year A1 certification from Lloyds