MARTIN’S TIME IN THE WORKHOUSE

The Workhouse in Boyle was built under the 1838 Irish Poor Law; a law which in its intention was neither constructive nor benevolent. Poverty was a nuisance and poor people were dealt with as public nuisances and so were treated like criminals. Jails were for criminals and the workhouses were built and run on prison lines for the poor. The name “workhouse” was a complete misnomer as they were never places of work, but of detention.

In the view of George Nicholls, the English official on whose recommendation the workhouse was built, the sufferings of the poor were of their own creation and the remedies within their control. The workhouse was to act as a “test of destitution”, the relief provided there being less desirable than that supposedly obtainable by independent endeavour. This “test of destitution” principle made the workhouse worse than a jail. Since the standard of living of the Irish poor at the time could not have been more miserable, the punishment of the workhouse had to come from its discipline - the breaking up of families, the segregation of the sexes, the prohibition of alcohol and tobacco, and the scant and monotonous diet. Although workhouse ‘relief’ was available to everyone, only those in direst need took up the ‘offer’!

The Poor Law Union was administered by a board of guardians who were responsible for setting rates and collecting them from the landowners. The rates were levied on land and Lord Lorton, being the biggest landowner in the district, paid £3,600 annually into the Unions of Boyle and Sligo.

Built like other workhouses, to the design of architect George Wilkinson, Boyle Workhouse opened its doors on 31st of December, 1841, with accommodation for 700 people. It was a limestone building in three main parts. At the roadside was the entrance lodge where people were admitted and in this block was also the Board Room where the Guardians held their meetings. Behind this building and separated from it by a courtyard was the main building, also known as the able-bodied quarters. Behind this again was a further block comprising the infirmary which was intended only for those who took sick after entering the workhouse. Sickness itself was not a valid reason for admittance.

The rough institutional character of the workhouse is evident in the quality of the furniture and utensils in use there. Most of the beds were ‘double’, except for the infirmary. The so-called double-beds were three feet ten inches wide (1170 mm.), and the single beds two feet four inches (710 mm.)

The diet was worse than in the prisons of the time consisting of two meals a day of very high starch content. Food was supplied to the workhouse by contract to the lowest bidder - at times as low as ninepence per head a week. The inmates bore the mark of poor feeding in their looks, utter despair in their demeanour, and many suffered from inflammation of the eyes.

The workhouse then was the bane of the life of every poor person. A contributor to the ‘Nation’ wrote; "the Workhouse . . means that the poor peasant shall leave his fireside and his home forever, enter those cold and pitiless walls where poverty is branded on the brow where he would be parted from his wife and children and friends, and which he must never leave, except to fill a pauper’s grave, or wander as a vagabond over the earth.”

With the full brunt of the Great Famine, no longer could the workhouses be called a ‘test of destitution’, but rather a sad refuge for desperate people. From these years date the horror stories of mass pauper graves, coffinless corpses, and trap coffins with hinged bottoms so that the corpse could slip into the grave and the coffin be re-used for other burials.

In Boyle, the dread of the workhouse was so strong that even during the worst of the famine, many people actually faced starvation rather than enter its walls. Others even left it to die of starvation in their homes. This aversion seems to have been stronger in Boyle than in neighbouring unions. During the worst years, while workhouses at Roscommon and Sligo were extremely overcrowded, the Boyle workhouse had only about 200 more than its designated number of inmates.

Boyle Guardians coped badly during the famine years; partly because the rate of collection almost broke down as many landowners were unable to collect rents from the tenant farmers, and partly because they applied the “workhouse test” too rigorously. They offered help within the workhouse, but if people refused to go in then they got little or no outdoor relief. Many cases of severe distress went uninvestigated and where outdoor relief was given it was not enough to sustain life - a family of five receiving as little as 12 pounds of meal a week. So many deaths from starvation were reported in the Boyle region that an official investigation was held and the Board of Guardians dissolved and replaced by vice-guardians. After this, the number receiving outdoor relief went from 7,000 to 19,000 in one year!

* * * * * * * *

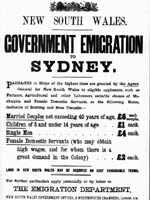

For Martin, the next seven years in the workhouse seemed like a life sentence in prison with no possibility, ever, of deliverance. Then, in September of 1857, the unthinkable happened; and despair turned into unbelievable joy. A Poor Law official arrived at the Boyle Workhouse with papers from the New South Wales Immigration Commission which comprised passage paid to Sydney, a remittance of ten Pounds, sufficient to outfit him for the journey and have some left over for the voyage, and a short note from Catherine saying she had kept her promise and longed to see him when he joined her in Sydney.

For Martin, the next seven years in the workhouse seemed like a life sentence in prison with no possibility, ever, of deliverance. Then, in September of 1857, the unthinkable happened; and despair turned into unbelievable joy. A Poor Law official arrived at the Boyle Workhouse with papers from the New South Wales Immigration Commission which comprised passage paid to Sydney, a remittance of ten Pounds, sufficient to outfit him for the journey and have some left over for the voyage, and a short note from Catherine saying she had kept her promise and longed to see him when he joined her in Sydney.It is interesting to note here that many of the female Irish orphans were better educated in the wily ways of the world than at first was evident and were very successful in negotiating with the immigration officials in Australia to bring out other family members.

for Sydney under Capt. James Connell. By this time, the fast ships of the day, in a hurry to capitalise on the business promoted by the On 30th September 1858, he embarked on H.M.S. Stebonheath goldrush, were taking the Great Circle route to Australia pioneered by James Thomas Towson. Using the ‘Roaring Forties’ they were completing the journey to Sydney, non-stop, in under 80 days.

goldrush, were taking the Great Circle route to Australia pioneered by James Thomas Towson. Using the ‘Roaring Forties’ they were completing the journey to Sydney, non-stop, in under 80 days.

Towson: “ I have endeavoured to impress navigators with a sense of the mistake they commit in considering the Cape of Good Hope as on the way-side of their best route to Australia. It is not only a long way out of the best and most direct track for them, but the winds also to the north of the fortieth parallel of south latitude are much less favourable for Australia than they are south of this parallel.”

Captain Connell was more of the older school who followed the route still recommended by the august lords of the Admiralty by way of the Cape of Good Hope turning east at the 39th parallel to run down to Australia. The ‘Stebonheath’ was no clipper and took 152 days to reach Sydney having stopped at Pauillac near Bordeaux at the start of the voyage to effect repairs after storm damage and then Teneriffe and Capetown. She was a cargo ship of 1013 tons built in Hull, but for the emigrant voyages, temporary two deck accommodation was built ‘tween decks to be jettisoned on arrival in Sydney for a return cargo of wheat and wool. On arrival in Sydney, Captain Connell received a draft from the immigration agents made up of £5,087/5/0 for passengers landed alive and £8/1/6 for those who died during the voyage.

For Martin, the next seven years in the workhouse seemed like a life sentence in prison with no possibility, ever, of deliverance. Then, in September of 1857, the unthinkable happened; and despair turned into unbelievable joy. A Poor Law official arrived at the Boyle Workhouse with papers from the New South Wales Immigration Commission which comprised passage paid to Sydney, a remittance of ten Pounds, sufficient to outfit him for the journey and have some left over for the voyage, and a short note from Catherine saying she had kept her promise and longed to see him when he joined her in Sydney.

For Martin, the next seven years in the workhouse seemed like a life sentence in prison with no possibility, ever, of deliverance. Then, in September of 1857, the unthinkable happened; and despair turned into unbelievable joy. A Poor Law official arrived at the Boyle Workhouse with papers from the New South Wales Immigration Commission which comprised passage paid to Sydney, a remittance of ten Pounds, sufficient to outfit him for the journey and have some left over for the voyage, and a short note from Catherine saying she had kept her promise and longed to see him when he joined her in Sydney.